ANN ARBOR (WXYZ) — As the federal government shutdown continues the trickle-down effect is going to have larger and larger impacts on metro Detroit.

On Friday the Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory (GLERL) office doors were locked — a sign on the door read: “Due to lapse in government funding this facility is closed.” Those who know the work that would typically happen inside warn that the longer the shutdown continues the more vital work is threatened.

“There’s a lot that goes on behind-the-scenes that people aren’t aware of,” warned John Bratton, a senior scientist at LimnoTech — and a former Acting Director of the GLERL lab.

Bratton is now in the private sector, but even he is noticing a change after the shutdown has extended into a second week. While anyone logging onto the NOAA (National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration) website will get a warning that the website isn’t operable during the shutdown, he and other scientists can’t even get emails returned. NOAA is full of researchers who work hand-in-hand with universities, private companies and Canadian counterparts exchange information. Since the shutdown began plenty of data is no longer being tracked, websites that are used and shared between agencies are offline and the workers are no longer allowed to work.

This week Bratton got a boiler-plate email in response to questions about a grant proposal. With the deadline approaching, there’s no certainty that the deadline will move or that anyone can be prepared.

His latest email is just the tip of the iceberg. Researchers that would typically be planning, and preparing, for this Spring’s research projects are locked out of their buildings. They’ll have a condensed time frame to prepare. Some research, Bratton notes, is likely being lost right now — when he was in charge of a government lab during the last shutdown he noted a number of research projects couldn’t be recreated at a later date, the work wasn’t recovered.

Perhaps even more concerning, the staff that’s deemed non-essential during a shutdown that could become essential in an instance. One example, if an oil spill occurred on the Great Lakes the staff that forecast currents are currently locked out — they would be an integral part of a cleanup effort, but they aren’t working right now.

“There were events that happened during the shutdown that required calling people back from furlough status to respond to them during the last shutdown,” Bratton said.

Those events included a hurricane, and a toxic algal bloom that threatened water supplies — because there aren’t middle managers working during the shutdown it was a long process to get employees back on the job. That said, when workers returned to work their support staff was missing.

“You’re just trying to do your job, and you can’t do your job,” Bratton said. “There’s a lot of things going on in Washington that you don’t have anything to do with.”

On Friday the U.S. Office of Personnel Management signaled that the shutdown could continue longer than many expected. The group tweeted out sample letters for federal employees going without pay to send to creditors, mortgage companies or landlords asking for relief from payments as they are furloughed.

Each sample letter ends with, "I appreciate your willingness to work with me and your understanding during this difficult time."

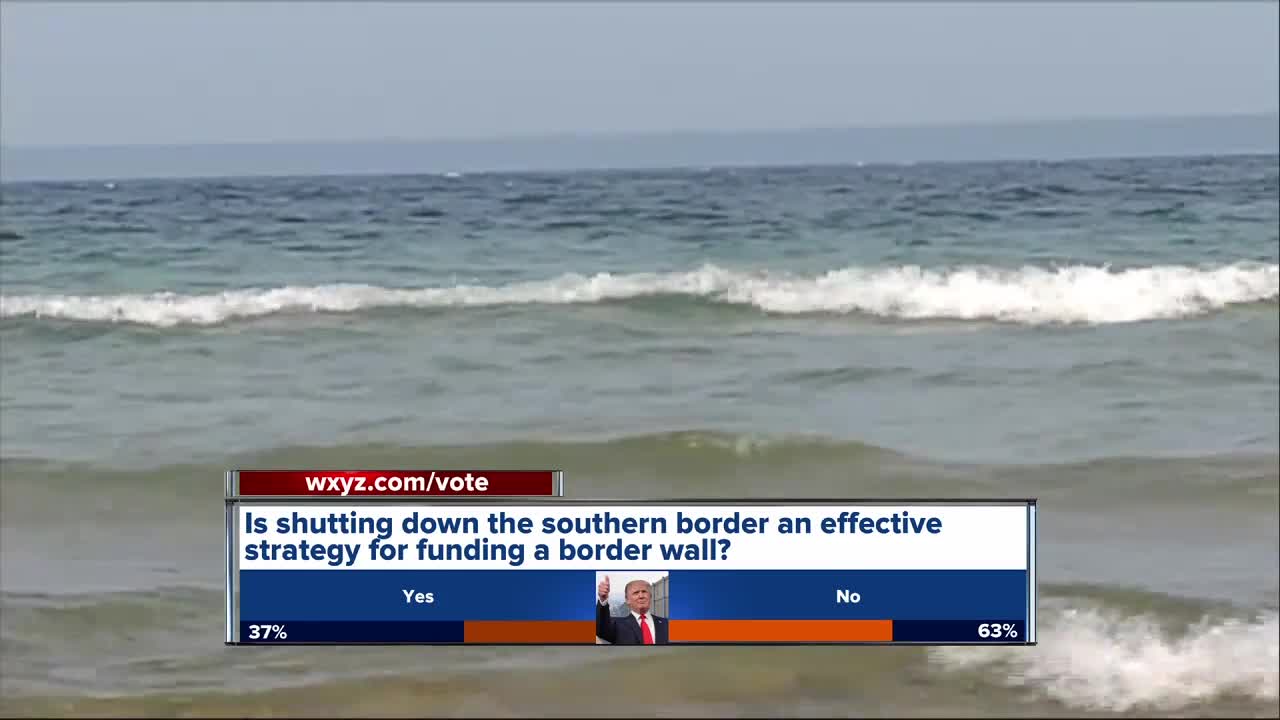

Meanwhile, the President has threatened to shutdown the southern border altogether in an attempt to force Democrats to change their stance and approve more money for a border wall — the wall has been a sticking point in the funding bills that has the White House and Senate Democrats at odds.

“Whatever it takes,” said President Trump, “we’re going to have a wall. We’re going to have safety.”

The talks continue, but as Friday came and went it became more likely that the government shutdown extends into 2019. In Michigan, that doesn’t just mean people going without pay — it also means growing concern for the people who work to protect the Great Lakes.