Few may have noticed, but Detroit was the center of a terrorism exercise that drew in the Army National Guard, U.S. Coast Guard and countless other state, and local authorities to discuss what would happen if a chemical attack happened.

Unlike war games that draw several hundred with a “boots on the ground” approach, the work went largely unnoticed by the public because this was a “table top” exercise — the idea was to form a number of challenges and see how military leaders would react. Among the local leaders and top brass were PhD students and top planners.

“The federal leaders, like ourselves, are educating the local officials about what capabilities we have,” explained Major General Michael A. Stone of the Army National Guard 46th military police command. “They learn about our response times and how many forces can get here to help save lives on Detroit’s worst day.”

Typically when you think of the National Guard you think of mass responses to flooding, hurricane damage sites or fighting overseas. Major General Stone said that last week’s exercise was key because it allows his personnel to get in a mindset outside of the work they’ve been performing in the Middle East, but also to get a real-life look at what things look like up close. Viewing buildings, tunnel systems and important landmarks on a map can only get you so far, the table top exercise that took place this month gives his troops a better understanding of real-life scenarios.

“We’re just doing the best we can for, well, if God forbid the worst events happen,” he said.

That included a rare underground look inside tunnels owned by Detroit Thermal. Crews vented a section of the 100+ year old tunnels to clear the way for National Guardsmen to explore underground and get a better idea of how they could play into an attack whether someone uses them against the city, or if they could even be used to rescue people.

“You don’t think about subterranean in a major metropolitan city, but you’ve got 20 miles of tunnels under the city that you don’t think about,” said Stone.

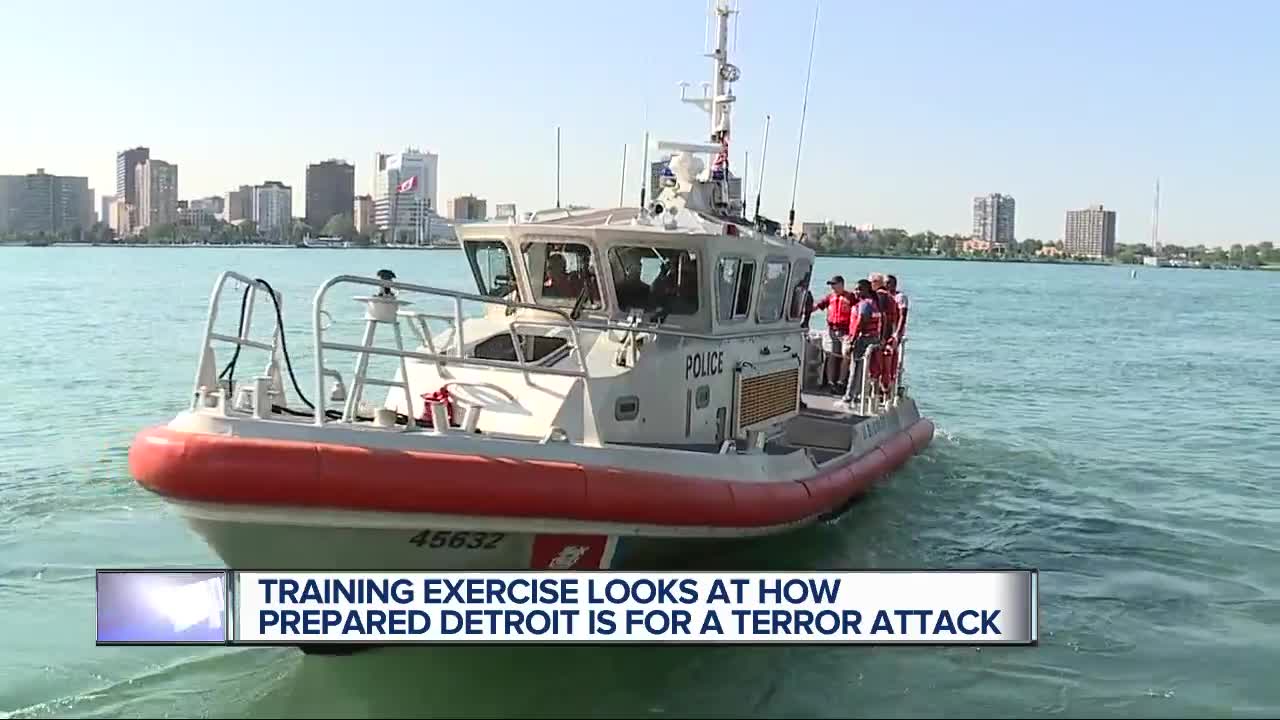

The U.S. Coast Guard also took teams of a dozen or so members of the National Guard alongside the Detroit River — a unique aspect of the city that gave more purpose behind the events. Typically war games are played out in rural areas, but the exercises in Detroit added real-life components including the Detroit River, a border with another country, etc. It’s those types of challenges that you may not think of when you act out a terrorism drill outside of a metro area like Detroit.

“You also have changing technologies,” explained Lt. Benjamin Chamberlain of the Coast Guard. “You need to adapt and utilize new tech, so we’ve been working with the EPA and doing environmental monitoring for them so we can understand, ‘If there’s a chemical release, how does it react?’ We can work with them to understand how much of the river would have to close down if there’s an impacted area.”

As leaders pointed out there’s things you don’t naturally think about when it comes to large events. For instance, during the September 11 attacks on New York City first-responders had to climb flights of stairs for hours — there’s now research going into how people can approach a building from the roof and clear it from the top down.

Then there are the more simple problems: if a mass casualty event happens, where do the wounded go?

Cities regularly train for hundreds of injuries, but when the number swells to tens of thousands the need grows exponentially for outside triage units. That’s when training matters the most.